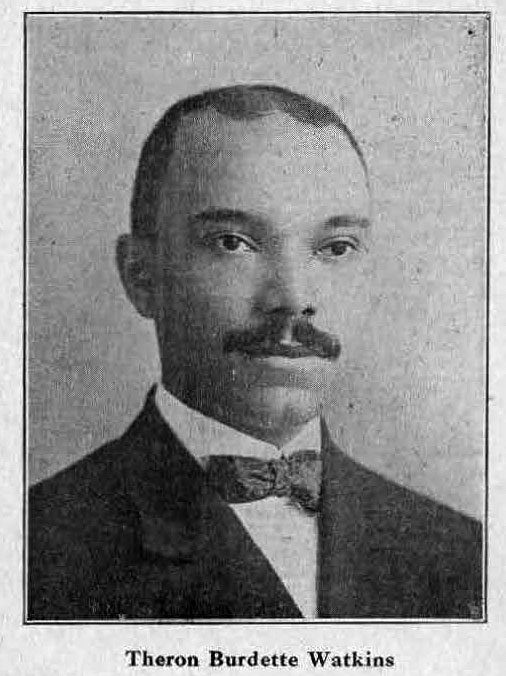

Theron B. Watkins House

2506 Benton Boulevard

Theron B. Watkins

Biography from “Taking Up the Black Man’s Burden” by Charles E. Coulter

Theron B. Watkins (''T. B." to many), like most of the prominent African Americans in the two Kansas Cities, was not native to the area. He was born March 24, 1877, on a farm about thirty miles east of Indianapolis, near the farm community of Charlottesville. His father, John D. Watkins, died when Theron was five years old , and his mother, Martha Lyons Watkins, moved Theron , his brother, J. T., and two sisters a few miles south to Carthage, Indiana. Theron and the rest of the Watkins children attended the Carthage public schools, and Theron eventually graduated from high school with class honors. From Carthage, Theron followed a circuitous path to Kansas City. Watkins worked his way through Indiana State University in Terre Haute and received his degree in political economy. As did many young ambitious and intelligent black men of the period, Watkins worked first for the Pullman Company. Then he began working for a white undertaker, Raymond Johnson. From Johnson, Watkins received the motivation for opening his own funeral parlor. In 1908, Watkins graduated from the Cincinnati School of Embalming, and in 1909, he and J. T. moved to Kansas City. Within a few months they had opened Watkins Brothers Funeral Home at 1729 Lydia Avenue. By 1920, despite J. T. Watkins's death in 1917, Watkins Brothers was one of the most successful black businesses in the two Kansas Cities.

Theron Watkins quickly moved into leadership roles in the black community. Theron, who was described by one contemporary as a gifted orator, served on the original board of directors at Perry’s Sanitarium and in 1913 was one of the leading fundraisers for the establishment of the Paseo YMCA. He also sat on the Miles Bulger Industrial Home for Negro Boys in Jackson County and by 1921 was serving on the board of directors at Wheatley-Provident Hospital. He was one of the featured speakers at fundraising event for LeRoy Bundy of East St. Louis. Watkins's speaking ability, his business acumen, and his commitment to the Eighth Ward made him a perfect candidate in the eyes of many of his contemporaries Even those individuals who had been mentioned as possible candidates for the Republican nomination rallied to support Watkins. E. C. Bunch, who, according to oral tradition in the black community, was used by white Republicans to split the African American vote and thus thwart Watkin’s candidacy, came out publicly for Watkins in the latter stage of the campaign. Nevertheless, white Republicans; still a significant presence in the ward although outnumbered better than two to one, controlled the canvass enough to select a white candidate. Watkins's supporters were fun. Shortly after the Republican gathering, five hundred African Americans gathered at Highland Avenue Baptist Church, and Theron B. Watkins was elected by the gathering to run for alderman as an independent candidate.

A campaign committee, led by E. C. Bunch, was appointed, and immediately petitions were drawn up to get Watkins’s name on the April 4 ballot. Nelson Crews and Chester A. Franklin quickly threw the editorial weight of their respective papers behind the Watkins candidacy. Crews, in particular, was infuriated by the outcome of the Republican canvass. In no uncertain terms, he argued that a ward that was two-thirds black should have an African American representative. In Crews's mind, “justice and right” demanded support of Watkins by every "red-blooded self-respecting" black man and woman in the Eighth Ward. Watkins's campaign, at least for that one month in I 922, eliminated divisions of gender, geography, and status within the African American community. From the outset, he stated that if elected, he would represent more than the Eighth Ward; he would represent all of the forty thousand African Americans on the Missouri side. Watkins drew support from African Americans from all walks of life; even his competitors in the funeral industry rallied to his side. Early in April, the Undertakers' Association of the two Kansas Cities-including C. H. Countee, A. T. Moore, and Adkins Brothers Funeral Home-endorsed Watkins. Watkins's campaign was not limited to African American males. Nannie C. Bunch, wife of E. C. Bunch, and Eva Fox, both community activists in their own right, were among the speakers at Highland Baptist arguing for a black candidate to represent the Eighth Ward.

Nelson Crews, meanwhile, continued his fervent support for Watkins. The issue became, in Crews's hands, twofold: Watkins's more-than-sufficient qualifications to represent the ward and the racial pride and self-image of Kansas City's African American communities. In an editorial three days before the election, Crews spelled out the situation:

One of the most gratifying features of the municipal campaign now being waged in this city is the evident determination on the part of the masses of our people to study, reason and THINK out for themselves the best method by which to serve the race and the Republican party. It has been amply demonstrated that the time has long since passed when white men can label any collection or conglomeration the Republican ticket and win the support of thinking Negroes. Our people are now demanding that men shall be measured up four-square to the principle and policies of a square deal and fair treatment to all races that go to make up American citizenship or they cannot hope for the support of the THINKING NEGROES of this community.

Watkins's campaign was spectacularly effective but ultimately unsuccessful. When returns from the election were posted, Watkins had received more than 2,000 votes. The Democratic candidate for mayor, Frank Cromwell, however, won in a landslide and carried the entire Democratic ticket into office. Watkins's losing margin-some 170 votes-was the smallest of any of the races. The Republican candidate from the Eighth Ward received just 800 votes.

Watkins's career of public service did not end that April day. He remained a supporter of many of the key institutions and causes in the African American communities of the two Kansas Cities. Before 1920, he invested with Reuben Street in the Street Hotel; sometime in 1924 or 1 925 the partnership was dissolved. Watkins was instrumental in the founding, with H. O. Cook, of a cooperative credit union, the People's Finance Corporation, and he served as the cooperative's president for almost twenty years. In 1941, he was the only African American appointed to the newly organized Kansas City Housing Authority, and during World War II he served on the Selective Service Board. In 1944, Watkins unsuccessfully ran for the Missouri legislature. He also was an ardent supporter of issues affecting African American youth. As noted above, he was instrumental in the operation of the Miles Bulger Home. He also supported a number of African American students financially. In addition, Watkins was interested in athletics, and he was one of the founders of the Gateway Athletic Club for black youths. He died September 4, 1950, shortly before the new Watkins Brothers funeral parlor at Eighteenth and Benton Boulevard was completed.

SourceS

Coulter, Charles. Taking Up the Black Man’s Burden. Columbia: University of Missouri Press 2006.