swope park Golf Course

6900 Swope Memorial Drive

Swope Park Golf Course

From Author Mark Wagner, “As I See It: In the heart of the Heart of America.”

Every great golf course story ends with a rich industrialist murdered for his money, but I will come back to that.

For now, suffice it to say that in 1896, the wealthy industrialist Thomas Swope, who would be poisoned on his deathbed, donated 1,800 acres of high ground to Kansas City, and there established the city’s largest green space, Swope Park, encompassing soccer pitches, a treetop adventure park, and two golf courses.

In the spring of [2019], I had left behind my Worcester State University students at a conference to travel out of downtown Kansas City and to play Swope Memorial, a Tillinghast design. My students were presenting on our civic engagement projects at a national conference, and I had was playing hooky to pay my respects to a Tillinghast course. A Tillinghast! The very name rings like the lyre of Orpheus, singing of the early mythic days of golf in America.

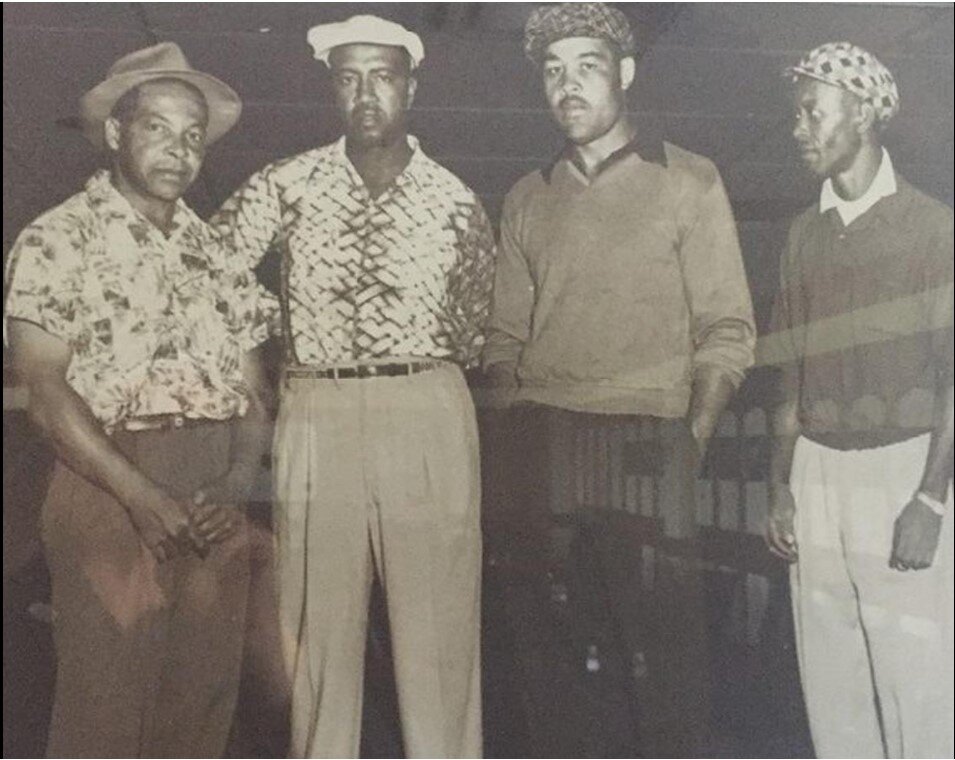

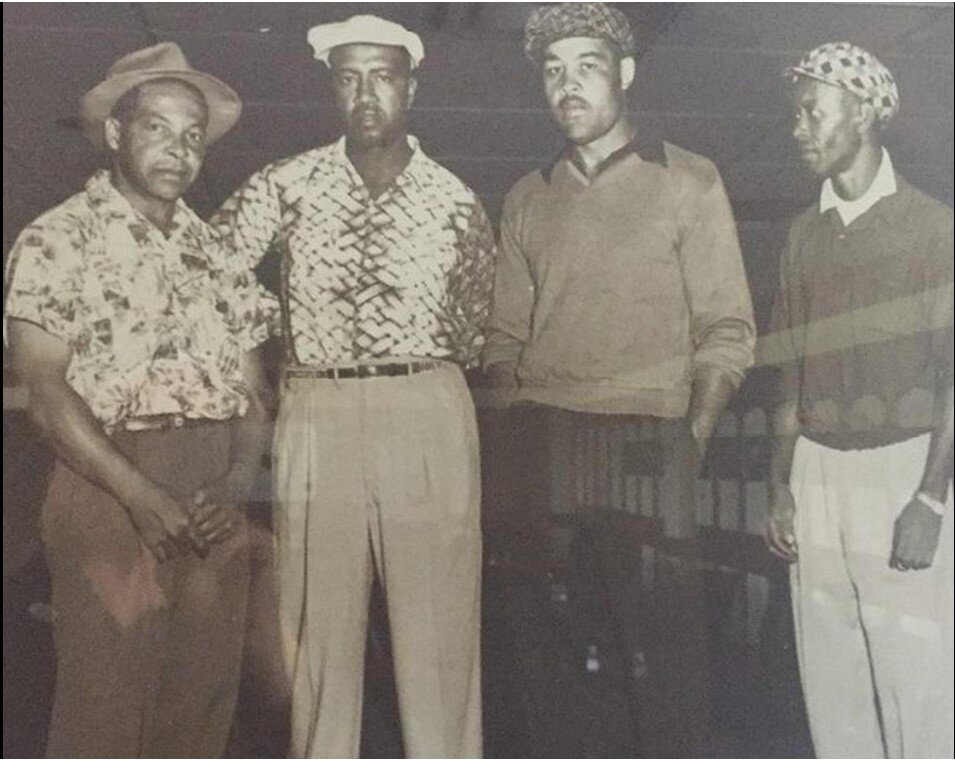

But on traversing the long winding and tree-lined road up to the clubhouse at Swope Memorial, and wandering around the clubhouse looking at memorabilia, I came on a picture of “The Foursome,” the four black men who had broken the color line, in March 1950, by non-violently paying for and the playing the White’s Only Course. I had come upon a thread of American history woven into a lush, hilltop course that climbs and falls and loops around the high point of Kansas City, the Heart of America.

To be sure, in uber-ing out of downtown and up the rolling hilltop called Swope Park, I bristled with the fascination with golf course architecture; to play a 1934 Tillinghast would ostensibly bring me in touch with the legend who designed Beth Page Black and Winged Foot and Ridgewood Country Club, (where my dad once bragged about punting a round).

Tillie, as Tillinghast was known, was not only a designer but a poet and a humor writer who had a column called “The Humor of the Game.” Yes, Tillie knew that golf could be absurdly funny (something DJ and Brooks might want to consider in all their seriousness), and certainly Punters like myself need to take a bit of that absurdity with us when approaching the tee box and begin our daily slices.

As a designer, Tillie was dedicated to creating courses that were practical for the average player, but exacting to the expert. Tillinghast was also not afraid of designing around water and was an early adopter of the island green, which you won’t find much of outside America. In my early memories, I rode with my grandparents as they played Shawnnee and they had to hit a ball over the Delaware River!

We all are familiar with the dreaded magnetic water. Tillie is in part to blame. And he makes no bones about it: About taking chances, Tillinghast wrote, “Modern golf presents distances and hazards which say to everyone ‘you may,’ but to the expert who is attempting par figures their demand is ‘you must.’ ”

Interestingly, looking over the Tillinghast Archives, Tillie can also be found talking about Free Golf! Now like free beer, free golf can now be cast off as a joke, but apparently, there was such a thing. Here, in his 1917 brochure, Planning a Golf Course, he writes, “it must be remembered that those who frequent free course are not so prone to observe the strict ethics of the game as others, and consequently in planning free courses, dangerous parallel fairways and blind shots of every description should be avoided. Such features should not exist on any course, but particularly on one given over to the public.”

We would not be talking about foot golf, bigger holes, and junior tees if we had kept free golf alive, but that is a story for another day. On my day at Swope, I arrived at the field stone clubhouse and was greeted by American History, in particular our racial history, with a picture of what is known as The Foursome.

***

One cannot be a golfer and a lover of history without brushing up against how golf has played into the ugly history of race relations in America. Tiger Woods is only the latest embodiment of America’s fascination with and fraught history of having to answer for backwardness and bigotry. And so it is with Swope Memorial. In 1934, America was still grappling with the Jim Crow era, and there were two courses on the hilltop outside the freight yards of K.C. – One for blacks (No. 2) and one for whites (No. 1).

According to J. Brady McCollough, black people had been playing golf in Kansas City in the 1920s on a potato farm. Junius Grove, a black farmer known as “the potato king,” carved out a nine-hole course in Edwardsville, between Bonner Springs and Kansas City. The men who played on it formed a group called the Heart of America Golf Club. In the mid-’30s, the club was able to play at Swope No. 2, but only on Mondays.

In the late ’40s, black golfers realized their game was suffering from their isolation on course No. 2. No. 2 had half the holes and half the challenge of No. 1. According to The Call, Kansas City golfers were taking a “stinging beating” in regional tournaments. They were known as the “Scrawny-Driving” boys.

Like many sports, golf’s ugly history with regard to African-Americans is notable. Let’s not forget the Professional Golf Association had a whites-only rule until 1961. There remain many private clubs that have few black or Jewish members, and there are still a handful of prestigious clubs that do not accept women. All of which brings me to my encounter with courage at Swope.

Six years before Rosa Parks refused to go to the back of the bus, and 13 years before the “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, in 1950, Reuben Benton, George Johnson, Leroy Doty, and Sylvester “Pat” Johnson decided they were tired of waiting for America to welcome them. They were no longer going to wait for an invitation to play the white course at Swope Park. On Friday, March 24, 1950, they drove that winding road up the hilltop, walked in the clubhouse at No. 1. and laid their greens fees on the counter at the white’s course.

We can only imagine what was said, or whose eyes rolled. Jackie Robinson was spit on when he played. Bill Russell was called a gorilla. What was said to Benton, Johnson, Doty, and Johnson? Whatever else, it would have been something along the lines of, “You can’t play here.”

But on that day, four brave men left their money on the counter and marched past the practice green and toward the first tee of the No. 1 course. According to the folks I spoke with, the superintendent said called the police. But the first man walked to the tee, set his ball down and got into position looking out on No. 1, a subtle hole built around a swale that rises up to an elevated green. We can imagine the shocked white faces glared behind them all, as they brought their clubs back, followed through and advanced their balls and the black cause onto the fairway of what was previously a white’s only course.

As we can only imagine, change doesn’t come easy. As black men continued their attempts to play in the weeks, months and years after, without the help of the legal system, it became guerrilla war. Black men who played at Swope No. 1 had their tires slashed.

According to McCollough, the men of the Heart of America always had an answer, though. After a couple of weeks, foursomes became groups of five. At the beginning of a round, they would roll dice. The man with the lowest roll would watch the cars for the first nine holes, and then the highest scorer of the playing four would replace him.

And then came white flight. Even after The Foursome, Rosa Parks, MLK Jr., Brown Versus the Board of Ed, The Civil Rights Act, and the Obama presidency, we have work to do with respect to race. In K.C., after the 1950s the white folks took their money and left Swope No. 1 for the suburbs. The course came to disrepair, as did many others.

I have written about this in relation to the Franklin Park/William Devine course, which, like Swope, fell into disrepair as Roxbury went from a Jewish enclave to a black one. But like Franklin Park, Swope Memorial has been revived by dedicated city officials in the 1990s. Today, both William Devine and Swope are gorgeous public tracts. Swope improved to the point that in August of 2002, the USGA chose Swope as the site of their national championship.

O, and Old No. 2 was refurbished and turned into the Heart of American Golf Course and Tom Watson Golf Academy.

***

I have long been an admirer of the courage of Satchel Paige, who famously said, “never look behind you, something may be catching up.” It’s good advice, but maybe not possible for a country whose history is so checkered by warfare and strife.

The day I played Swope, I had left my students at a conference in the city that boasts the Negro League’s Hall of Fame, where Paige has his star. I had gone to Swope in search of a Tillinghast championship course, picturesque and challenging for the best public golfers and a good walk for Punters, but what I found instead was the Heart of the Heart of America, where history and courage meet.

And in that heart was a troubled history and the hopeful picture of the Foursome, another example of how our hope has been defined and carried by courageous men and women who stood up for and stand up for their rights.

I played a quick nine that day, so I could get back to my students who were presenting on our projects at the K.C. Convention Center. Before I left the course, I followed a pretty walking path down to the stately, Greek Revival Memorial to Thomas Swope. He’s the other hero in this story. By all accounts, Thomas Swope was a fastidious man, a lifelong bachelor who had amassed a fortune and left behind a magnificent park and a lasting legacy of thrift and industry.

In his last days, just short of his 82nd birthday, he died violently and suddenly at his brother’s lodge. Long story short, it turns out his doctor, Dr. Hyde, had poisoned him with strychnine and cyanide.

Why?

O, Money.

Dr. Hyde was tired and convicted, but he leaves us with this: Money, along with race, is another troubling subject in the Heart of the Heart of America, but a subject we’ll leave for another day. For now, raise a glass to Reuben Benton, George Johnson, Leroy Doty and Sylvester “Pat” Johnson whom had used their love of golf to advance us all toward a more perfect union.

Mark Wagner is a writer and musician and farmer living in Dudley, MA. He can be reached at markgwagner@charter.net