Joelouis mattox Residence

5645 Wayne Avenue

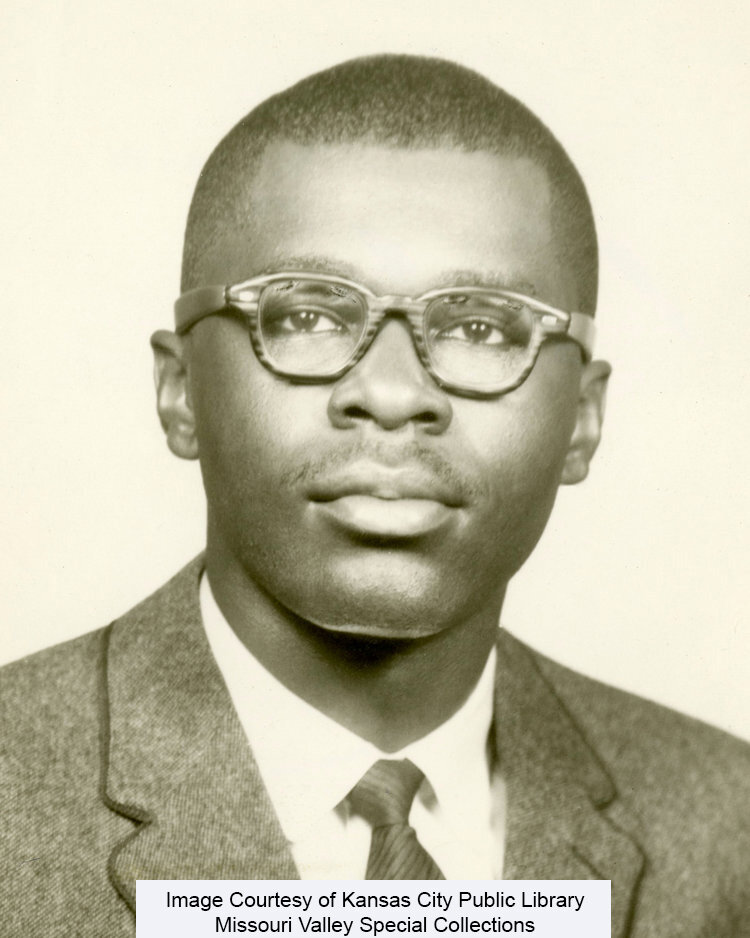

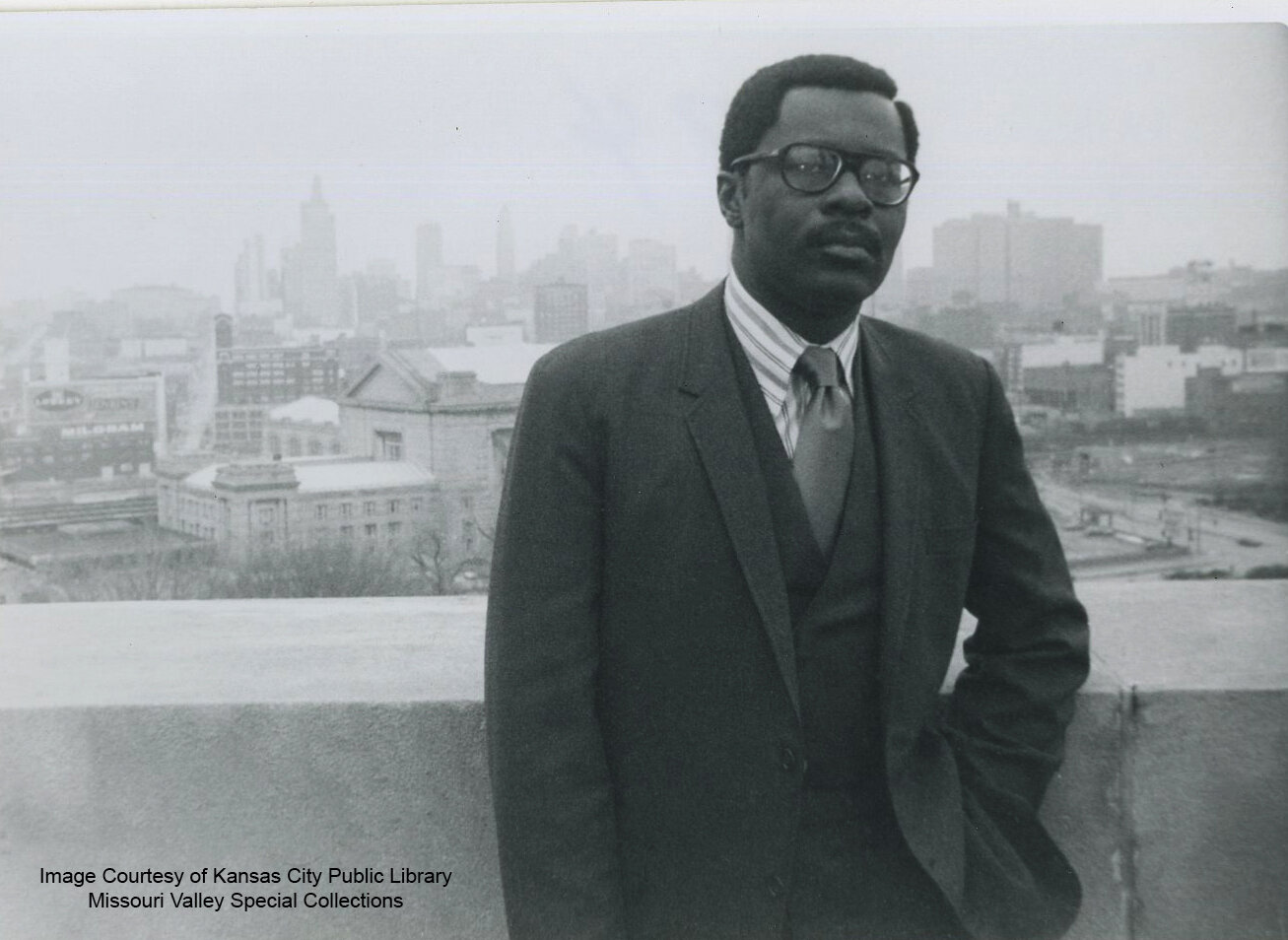

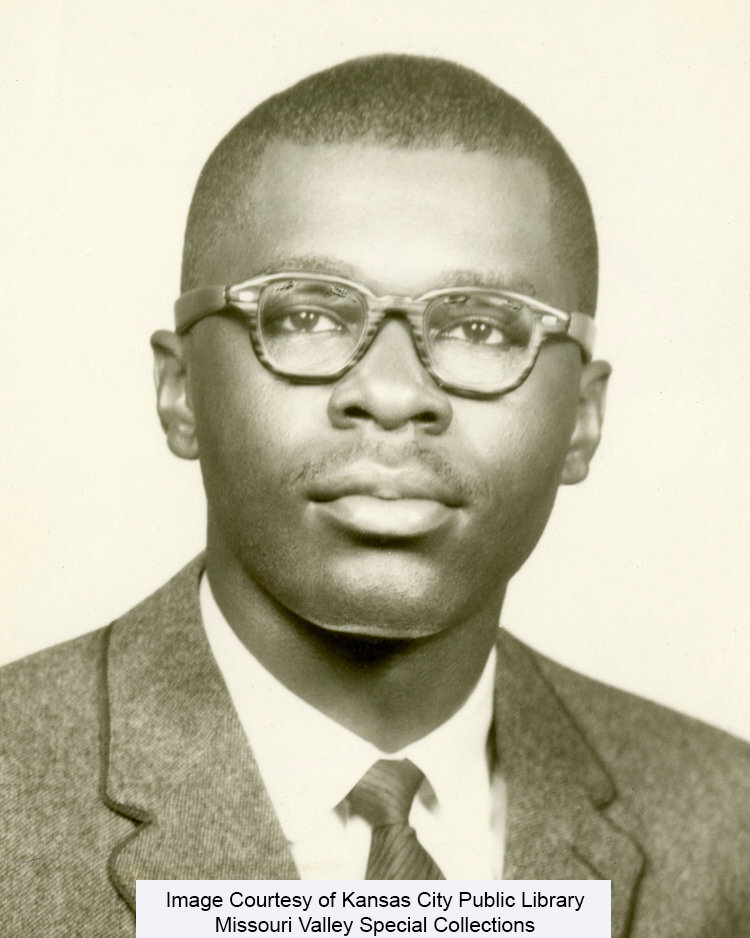

Joelouis mattox

From the Kansas City Public Library,

An Appreciation: Joelouis Mattox

Last modified: Tuesday, February 6, 2018

Whether absorbed in solitary research or standing at a podium, enlightening a roomful of listeners on some aspect of local African-American history, Joelouis Mattox was a familiar -- and eternally welcome – face at the Kansas City Public Library.

He was both patron and provider, speaking to audiences about Lincoln High School and the black enclave of once-segregated Swope Park known as Watermelon Hill. He recalled the battlefield valor of the Buffalo Soldiers and the singular sacrifice of Wayne Miner, the Army private who cruelly fell in France just hours before the end of World War I.

Last July, in what would be his last Library lecture, Mattox walked a crowd of 55 at the Southeast Branch through Kansas City’s “gloomy years,” the nearly four-decade period of the 1900s when bigotry and discrimination were accepted and even enforced. To know was to learn.

Mattox died this week at his home in southeast KC, a loss felt not only at the Library and in the African-American community but throughout the city and across cultural lines. He was, as former Kansas City Councilwoman Sharon Sanders Brooks told The Kansas City Star, “a treasure.”

Mattox had lived the gloomy years, growing up in segregated Caruthersville in southeast Missouri in the 1940s and ’50s. He toiled in the cotton fields when he was a teen, and also worked as a bus boy and short order cook at the Top Hat Café on Caruthersville’s Main Street.

There, in October 1953, came what he called “a moment that set the direction of my life.” Mattox helped serve breakfast to the visiting Harry S. Truman, who advised the then-16-year-old to finish high school and attend Lincoln University in Jefferson City.

Mattox did, studying history and government at Lincoln, serving as a student council officer and fraternity leader and twice making Who’s Who Among Students in Colleges and Universities. He went from school to service in the U.S. Army Signal Corps in Germany, and joined his mother in Kansas City upon his discharge in 1966.

He would spend more than three decades working in community development, housing management, and historic preservation (as a relocation specialist with the urban renewal agency in Independence, he once helped relocate Truman’s maid).

History remained his calling. Exhuming it. Preserving it. Preaching it.

Mattox was a volunteer scholar and historian at the Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center, historian for the city’s Historic Preservation Commission, historian of the American Legion’s Wayne Miner Post 149, and the William D. Matthews Scholar at the Battle of Westport Visitor Center and Museum in Swope Park. He made himself a local authority on the Steptoe neighborhood between Westport and the Plaza, where freed slaves once settled. And he was active in the Historic Kansas City Foundation and the Midwest Afro-American Genealogical Interest Coalition.

He became a Library fixture, regularly frequenting the Southeast Branch near his home and speaking there, at the L.H. Bluford and Plaza branches and at the downtown Central Library. “We build libraries for, and because of, people like Joelouis Mattox,” Director Crosby Kemper III said.

The Jackson County Historical Society gave Mattox its Cultural Heritage Award in 2007. A year later, he received the federal President’s Volunteer Service Award. And in 2014, Kansas City’s Human Relations Department honored him with its Martin Luther King Jr. Spirit of Unity Award.

Mattox considered his namesake, former boxing champion Joe Louis, a hero. As did many. Louis dominated the heavyweight division for nearly 12 years in the 1930s and ’40s, always maintaining what The New York Times called “a simple dignity.”

Mattox wore the name well.

Content provided by: Steve Wieberg, Writer/Copy Editor, Kansas City Public Library