Holy Name Catholic Church

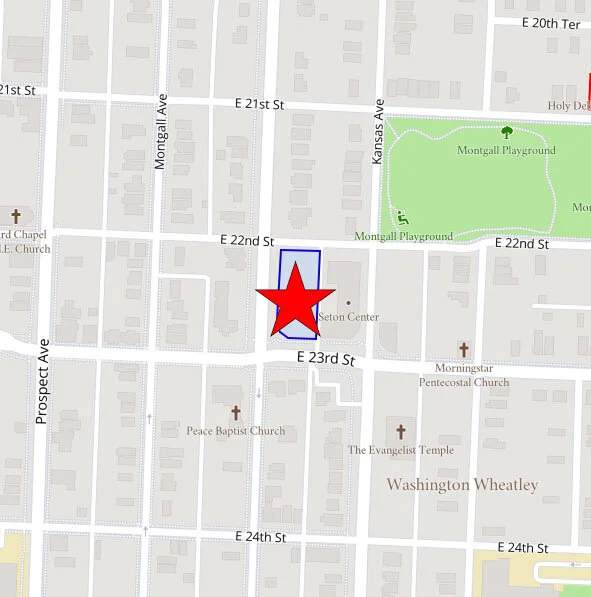

2800 E. 23rd Street (Demolished)

The Holy Name Parish, The Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Related Riot

The Holy Name parish was formally started in January 1886 with 35 members. The congregation picked the current site in an area that mostly served white upper and middle class population, though the number of white-collar workers outnumbered the blue-collar workers.[1] The congregation reflected this mix of class in its congregation. The site also was three blocks east of Prospect, the eastern dividing line between African Americans and other residences of Kansas City. Between 1910 and 1911, some African American families lived in the area around 25th Street and Montgall Avenue, southeast of the church. White residences tried to remove these families through a series of death threats, culminating in a series of six explosions in the area. However, in 1948 the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed racial discrimination in covenants and deed restrictions in the landmark case, Shelley vs. Kraemer. African American families moved into the area served by the church, and ultimately started changing the make up of the congregation as many white families moved out into the suburbs. By the time of the riots in 1968, the church was predominately African American.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929-1968), American clergyman and Nobel Prize winner, was one of the principal leaders of the American civil rights movement and a prominent advocate of nonviolent protest. He was assassinated in Memphis by a sniper on April 4. In 1969 James Earl Ray, an escaped white convict, pleaded guilty to the murder of King and was sentenced to 99 years in prison.

News of the assassination resulted in an outpouring of shock and anger throughout the nation and the world, prompting riots in more than 100 United States cities in the days following King’s death. The intensity of bereavement felt by African Americans may have been impossible for others to fathom, and as the new spread across the nation, violence spontaneously erupted in several urban centers.

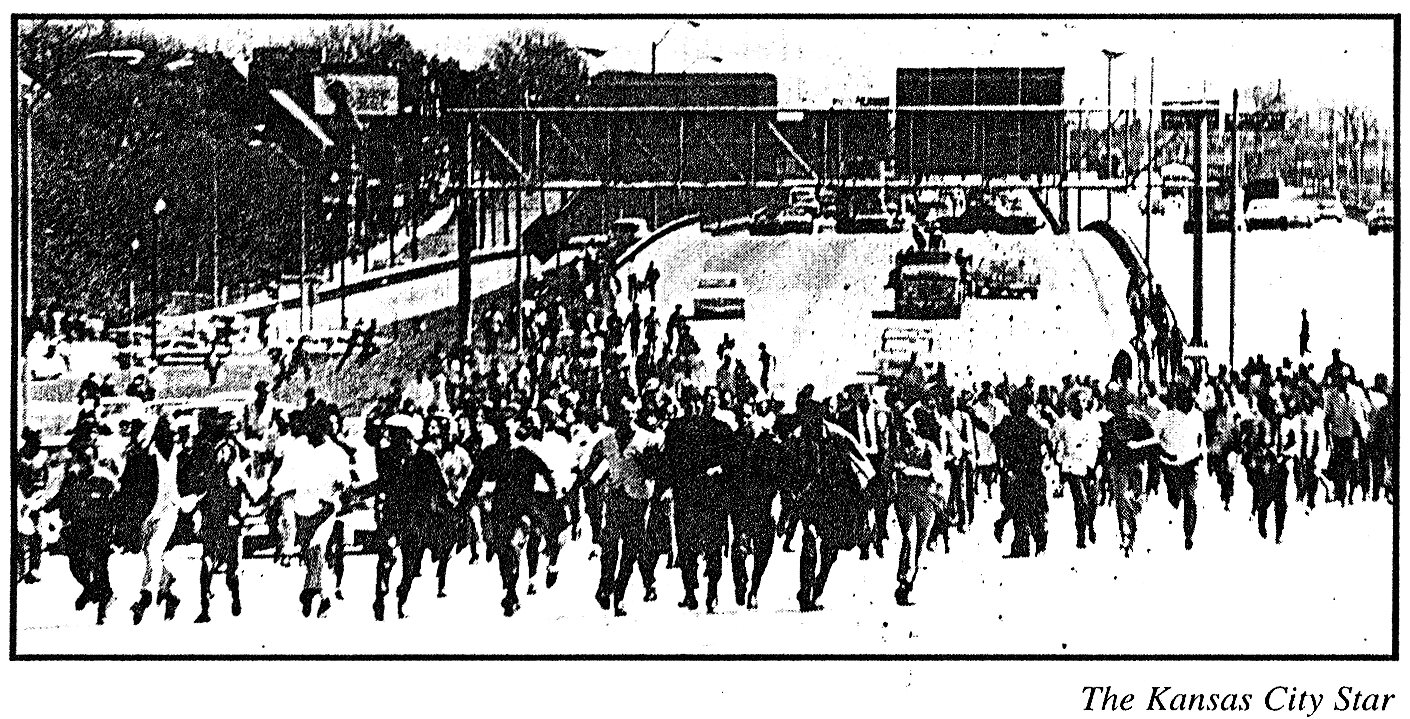

In Kansas City, the fourth “long, hot summer” had arrived two months early.[2] No violence initially erupted after the news spread. Many African Americans in Kansas City still suffered from poor housing conditions, school segregation, police racism, and other economic inequities. Anger and frustration among many of the youth bubbled up after a pivotal moment on Tuesday, April 9th, Kansas City decided to hold school, while other area schools were let out in observance of the funeral. The school district planned to hold a district wide assembly honoring the funeral of Martin Luther King, Jr. Over two hundred students at Lincoln High School left the school at the time of the assembly and marched south to join students at Central and Manual Schools.

Hearing that students were marching, Police Chief Clarence Kelley decided to move into a tactical alert, phase II of Kansas City’s riot control plan and notified Mayor Illus Davis. Following the announcement, reports of vandalism started coming in and the crowd gathered around Central school overturned several small cars and broke out windows. [3] The group then moved south to Paseo High School, another predominately African American school.

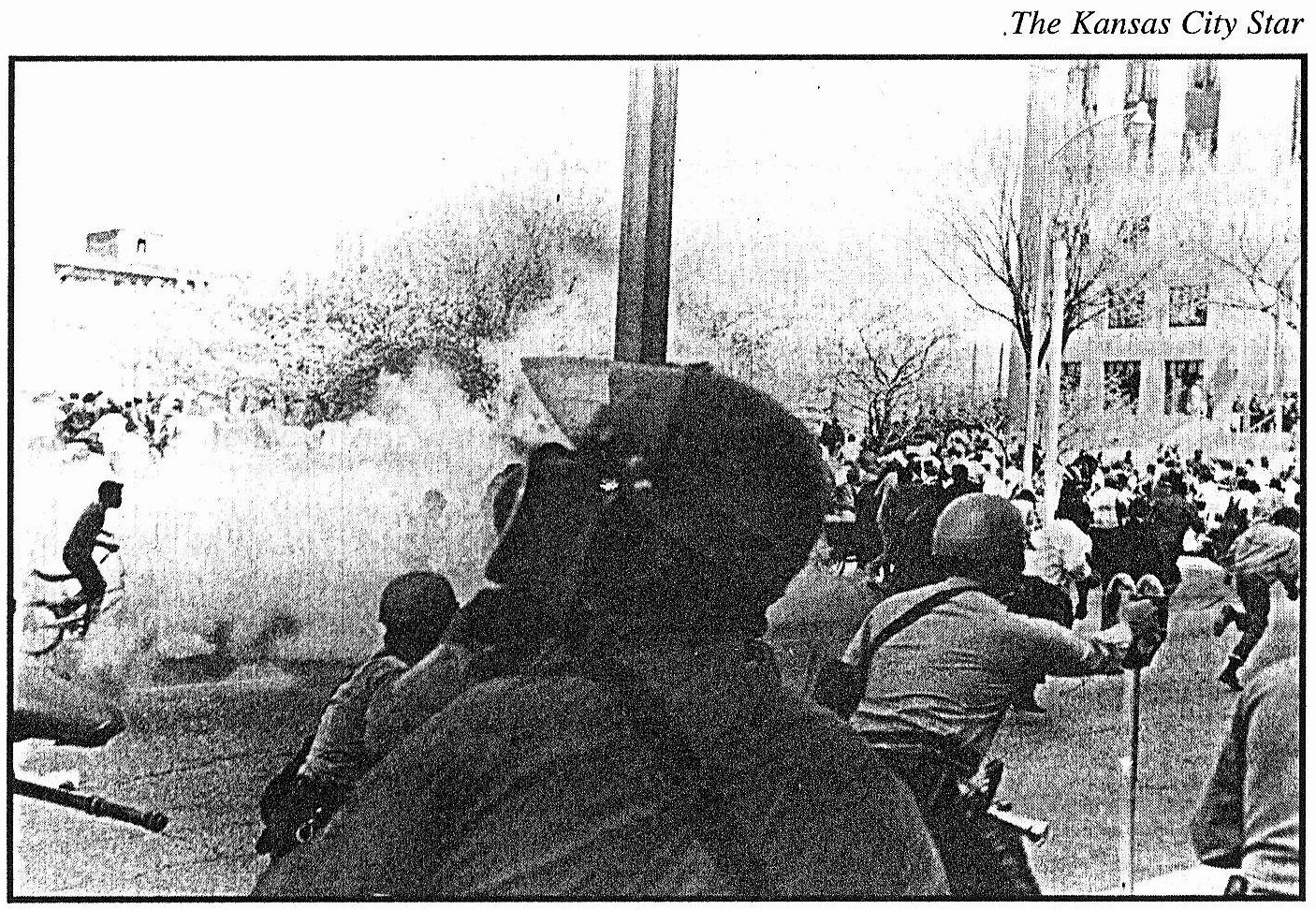

Eventually the police and the crowds clashed at 34th and Indiana, and tear gas was released into the crowds. The marchers became angry and marched back north to City Hall to demand an apology from Mayor Illuis Davis for the actions of the police. Chief Kelley placed the State Highway Patrol, along with police onto full alert. Mayor Davis called Governor Warren Hearnes and decided to activate one thousand Missouri National Guardsman.

The Mayor and many local leaders set up a podium outside of City Hall tried to talk to the gathering crowd. Cherry bombs exploding in the crowd frayed some of their nerves. It was during this time that KPRS radio announced a dance would be held at Holy Name Catholic Church and buses would ferry people from City Hall to the church. KPRS, which opened in 1950 was the nation's first Black station west of the Mississippi as a voice for the African American community. Many African Americans would be listening and hopefully news of the dance would spread. Organizers hoped the dance would help diffuse the situation. A couple of hundred marchers boarded the busses and headed toward the church.

One young man was dragged off a wall by police and rioters threw rocks at them. A can of tear gas was released, though no one knows if it was police or a rioter, but the result was that police released six more canisters into the crowd. The crowd scattered and bolted east. Many of the students on the bus narrowly missed the release of tear gas around City Hall.

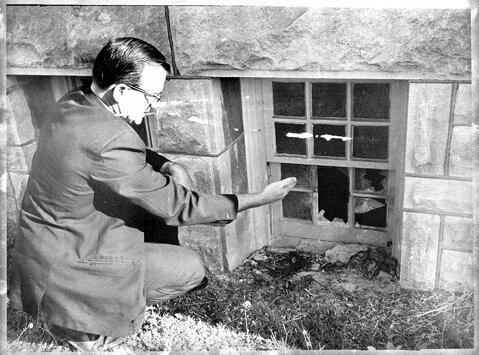

Though the event had the potential to diffuse the situation, police officers on the scene at the church did not know that a dance was in progress in the church basement when they responded to a disturbance call at the location. Students outside the church stoned the first policemen to arrive, and more police were summoned to the area. Officers, believing rioters had run into the church, began dispersing seven canisters of tear gas into the basement of the church. Chaos followed as police kicked in the windows and panicked dancers, unaware of events outside, search for the exits through clouds of tear gas. When the dancers emerged, they began stoning the police. Tensions at the church remained high for well over half an hour before crowds dispersed.

The riots lasted sporadically until April 11th, and the state of emergency was lifted by April 18th. In all over one hundred persons had been arrested. Two national guardsman, two firefighters, and a policeman had been wounded by sniper fire while over 150 fires had been set.[4] Though the Holy Name Catholic Church dance was only one the incidents that fueled much of the protests, the incident and the riot represented the culmination of the frustration of many African-Americans in Kansas City in their fight for equal rights. Due to rising expectations and the heightened activism brought about by the civil rights movement, the War on Poverty, and the Black Power movement, African Americans increasingly found the universal grievances regarding housing, employment, education, and the police intolerable. These riots, though violent at times, lead to many changes on how African-Americans were represented in government at all levels and was the start to a period of major advances to the Civil Rights of African Americans in Kansas City. Thus, this incident at the church represented an important event in the development of the Social and Ethic History of African Americans in Kansas City.

[1] Sherry Lamb Schrimer, A City Divided: The Racial Landscape of Kansas City, 1900-1960. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2002, p. 73.

[2] Joel Rhodes, “It Finally Happened Here: The 1968 Race Riot in Kansas City, Missouri,” Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 91 No. 3, April 1997, Columbia, MO: Missouri Historic Society, p. 295.

[3] Ibid., p.299

[4] Kansas City Times, 11 April 1968.

The Holy Name Catholic Church was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 25, 2003.